In 2019, beating up on Sam Mendes’ multi-Oscar-prevailing American Beauty, launched roughly 20 years in the past this week, is so painfully smooth that it seems unfair. The Best Picture winner has fallen largely out of style; it not often appears on critics’ lists of favored movies, and its reminiscence seems to have faded for most moviegoers, too. But in 1999, you were an outlier if you disliked the image while professing admiration for it was a manner of saying which you were hip to the modern American malaise—something, exactly, that turned into. As screenwriter Alan Ball

placed it in a 2000 interview, “It’s becoming more difficult and harder to live a real existence while we stay in a world that seems to cognizance on look.” Even even though, by using that point, we’d supposedly thrown off the inflexible social expectancies of the Fifties, Ball referred to that “in plenty of methods that are just as oppressively conformist a time. Ball wasn’t completely incorrect. But what, precisely, is a “proper life,” and how was engaging of the American Beauty revel in intended to help you stay one? American Beauty became a bad movie then, and it’s terrible now:

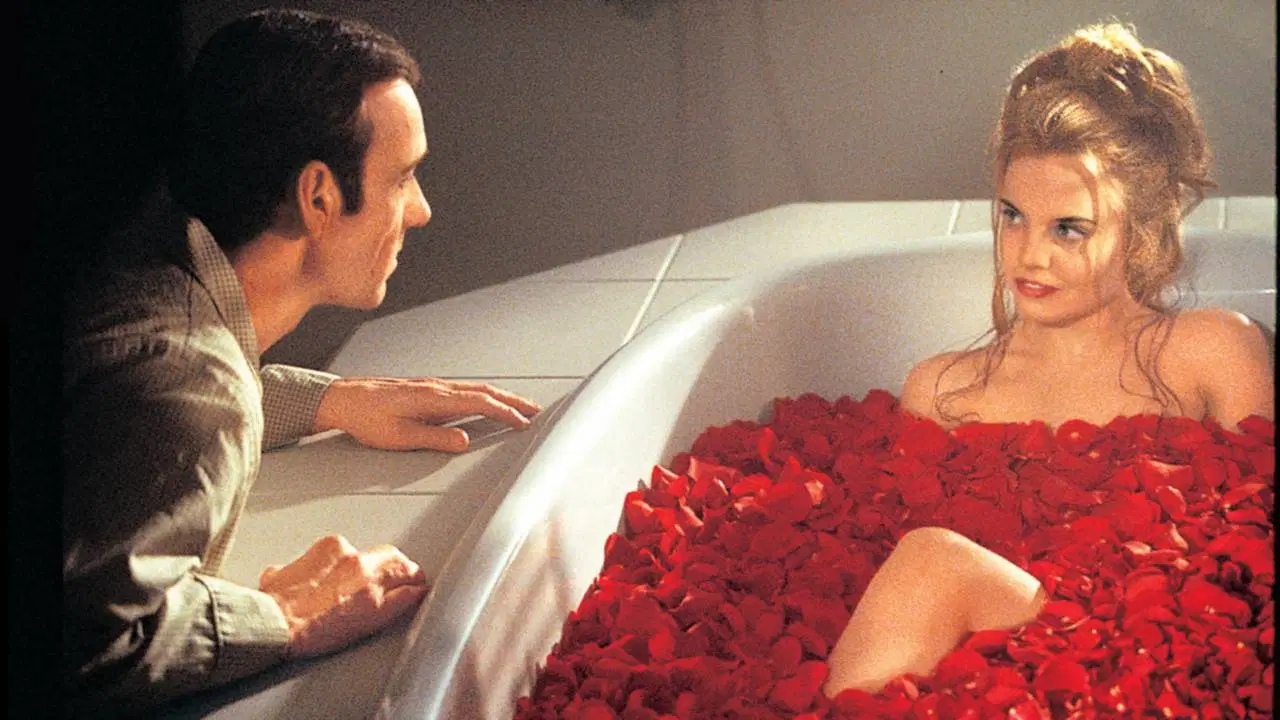

Kevin Spacey plays middle-aged suburban husband Lester Burnham, with an awesome however boring activity, who acknowledges how empty his lifestyle is. At the same time, he develops an obsession—one he nearly acts upon—along with his teenage daughter’s faculty buddy, played by Mena Suvari. The debut movie of director Sam Mendes (who’d already made his name in the theater world), American Beauty was crafted inside the most pristine and soulless way, manicured and buffed to bland tastefulness; it’s one of the most laughably square films approximately the destructiveness of conformity ever made.

Characters are saddled with moony faux-philosophical communication (“Sometimes there’s a lot of splendor inside the world I feel like I can’t take it”) or signpost language loaded with portent (“All I know is I love firing this gun!”). Generally, extraordinary actors deliver performances as tortured as sailors’ knots: Annette Bening, as Lester’s spouse, Carolyn, is a shrill, brittle, sexually repressed mother and actual-property agent, a cartoon stretched to the max. As menacing neighbor Colonel Fitts, Chris Cooper signals “uptight marine” by way of merely looking constipated. Spacey brings all of the edgy anxiety and brittleness his position needs of him; however, no longer even

he can negotiate the movie’s unearned “Gosh, lifestyles is lovely in the end!” shift, which swerves at us out of nowhere. And the film’s visuals nearly beg for banal scholar-time period paper evaluation. Crimson American Beauty roses organized stiffly in bowls during the residence, in nearly every scene; a gleaming purple front door that’s the most effective distinguishing characteristic of a residence outdoors that’s otherwise numbingly restrained; a scarlet blood splatter in opposition to a pristine white wall: Block that shade symbolism! Many critics loved American Beauty upon its launch, and some certainly stand by way of it today. But it usually appears to be one of this movies-with-a-message that humans like or say they prefer because it looks as if the right stance to take at the time.

Maybe it’s more valuable now, two decades on, as a way of inspecting what attracts us to sure movies within the first area. Even when films are not excellent—regardless of how hard they’ll try to galvanize us with their labored artistry—they may be a form of the altar where we depart our indistinct, unspecified emotions of dissatisfaction or unrest. In 1999, the American economy was wholesome; the task boom became sturdy, and buyers were optimistic. When you don’t have an activity at all, your joblessness is your number-one problem. But if you have a great job, you may be nagged by using the feeling that it simply isn’t sufficient—it’s luxurious you could have enough money. And that not-having-enough is the disquiet from which Spacey’s character, Lester Burnham, suffers.

Lester is in his early 40s and lives in a stunning house, with a beautiful spouse. But he’s no longer simply asking himself, “How did I get here?” He seems to be pushing for a way out. His teenage daughter, Jane (Thora Burch), barely speaks to him, and their relationship grows icier. At the same time, she catches directly to the erotic overwhelm he has on her buddy Angela (Suvari), a lissome, flirty cheerleader. The latter knows precisely why men like her—though she’s additionally plagued with actual-teen insecurities, and even though she acts as if she’s geared up for intercourse, she’s in reality no longer. A new family actions in round the corner: Dad is Cooper’s uptight, abusive colonel; he’s